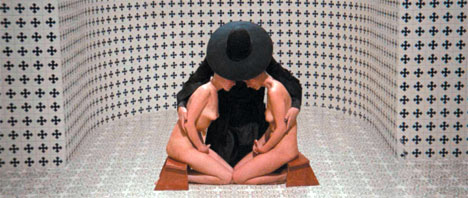

When you’ve seen a Jodorowsky film, you’re not going to forget it in a hurry. The strange imagery, philosophies and set pieces which seem entirely random and disconnected have a lasting impact; it stays with you regardless of whether you like it or not. These films were released during the popularity of LSD and Eastern philosophies amongst certain Western youth subcultures; it’s really no surprise that The Beatles were reportedly taken with ‘El Topo’, as were much of the Hollywood new wave of the time (Dennis Hopper for instance). Their lawyer, Allan Klein, even part financed ‘The Holy Mountain’, though ensured it remained undistributed and unreleased for more or less three decades afterwards (a DVD release of both films is imminent). I’m not sure the films have aged very well, or would strictly mean that much to those outside its obvious demographic. Both are surreal journeys, often beautiful, often disturbing, but totally unique.

When you’ve seen a Jodorowsky film, you’re not going to forget it in a hurry. The strange imagery, philosophies and set pieces which seem entirely random and disconnected have a lasting impact; it stays with you regardless of whether you like it or not. These films were released during the popularity of LSD and Eastern philosophies amongst certain Western youth subcultures; it’s really no surprise that The Beatles were reportedly taken with ‘El Topo’, as were much of the Hollywood new wave of the time (Dennis Hopper for instance). Their lawyer, Allan Klein, even part financed ‘The Holy Mountain’, though ensured it remained undistributed and unreleased for more or less three decades afterwards (a DVD release of both films is imminent). I’m not sure the films have aged very well, or would strictly mean that much to those outside its obvious demographic. Both are surreal journeys, often beautiful, often disturbing, but totally unique.‘El Topo’ centres on a lone man, dressed in black, riding through the desert with a naked boy. He reaches a massacred village (beware; there is a lot of blood everywhere in this film, as well as ‘The Holy Mountain’), and vows vengeance upon those who committed this savage act of violence. A group of oddballs harass him, assuming he’s easy prey, though they are summarily dispatched with ease, and he then goes in search of the sadistic colonel. Having watched both films, you sense a repetition of certain scenes. At this point, the colonel’s men dance with the clergymen like lovers would at a traditional dance, which is repeated with riot police and local male civilians in ‘The Holy Mountain’. Another of Jodorowsky’s favourite violent acts is directed at the colonel; his penis is chopped off. Several small details such as these make you think the director would be in dire need of psychoanalysis. The man leaves his boy behind, taking up with a woman he saved from being raped, who tells him she will only love him if he kills four gun masters, all of whom are peculiar in their way; one has a garden of rabbits which die as ‘El Topo’ approaches, another has two henchmen, one with no arms, the other with no legs (paraplegic/quadriplegic dwarves are very common in his work), and so on. ‘El Topo’s woman has a rival, both of whom seem to strip without any motivation, and there’s a definite attraction between the two. Again, the director indulges his fantasies big time. When told to decide between him and the second woman, the first chooses the other woman and leaves his for dead…where he is rescued by deformed folk who live in a cave. When he awakes, they ask if he will lead them out, echoing the mole proverb we heard at the very start of the film; that he buries around underground, looking for the Sun, yet when he reaches the surface, he turns blind.

These people are stuck underground, and cannot escape. He builds a tunnel with money earned from begging in the local town. This town is populated with oddballs and freaks; old women in daring underwear, yet with men’s voices, and male sheriffs in full make up with a sexual appetite for their male prisoners, but all have a distasteful appetite for branding, or hanging and shooting their slaves, watching men box with barbed wire around their gloves, and playing Russian roulette in church. The town’s new priest is….you guessed, it El Topo’s son, who has his own issues, and wants to kill his father (though he has to help him with the tunnel first). El Topo’s labours result in tragic circumstances however, when the cave dwellers run down to the local town upon completion of the tunnel, and are savagely gunned down. El Topo extracts his revenge, and sets himself alight afterwards as his wife (also a dwarf) gives birth. Don’t ask what any of it means though.

‘The Holy Mountain’ is a comparatively more straight-forward (though baffling still) journey towards enlightenment. A figure resembling Christ is stoned on a cross, but comes down, and ventures into a violent and repressive Mexico City, where he is first intoxicated so he can be used as a bust for Christ statues (he then destroys them all but one, carrying his own effigy) and then followed by a prostitute (Mary Magdalene?) and a chimp. All the while people are being randomly killed by police whilst tourists record it all, and a toad and chameleon re-enactment of the Conquest of Mexico remains the most popular tourist attraction. He ascends a huge tower in the middle of the city, which is inhabited by the Alchemist (Jodorowsky), who seems to be some guru of sorts, and begins the Christ figure on his path towards enlightenment. Quite why this involves distilling his excrement and then making him inhale the fumes, whilst a naked woman plays the cello and a pelican wanders around, I can’t say. The Alchemist is also taking seven others on this journey, each a member of the elite (police chief, architect, weapons designer, etc), each aligned to a planet. When the near mute Christ figure is the sanest by some distance, you can imagine what kind of people we’re discussing. The Alchemist explains that immortality can be achieved by climbing to the top of the Holy Mountain, so they embark on a long journey, with the prostitute and chimp closely behind. The individuals forsake their riches and worldly goods (a comment on the con tricks of cults?), shave their heads, take LSD, and try to overcome their fears (one woman is scared of heights, and is told to simulate making love to the mountain). Upon reaching the summit though, Jodorowsky plays the same cinematic bluff that has been used in ‘Taste of Cherry’, amongst other films; introducing the fact that this is a film into the narrative. Apparently speaking to those he has brought up the mountain, he speaks of the metaphorical aspects of the mountain, before we realise he’s really addressing US, when he asks the camera to zoom back. It’s a nice gimmick, and we’re not too displeased to have a little prank played on us.

It’s impossible to explain logically what’s going on in either of these films. Dispensing with conventional narrative, Jodorowsky fills the screen with numerous bizarre images in succession. Usually they have no obvious connection to each other, but you can’t deny that a fertile imagination is at work here. Maybe these are films that need to be seen rather than enjoyed, unless you’re happily under the influence of certain substances. I imagine the same people who dropped acid or LSD to ‘2001’ and saw it as the ultimate life-changing and mind-altering experience would have seen ‘El Topo’ and ‘The Holy Mountain’ in similar circumstances. I think Jodorowsky succeeds more with ‘The Holy Mountain’. His political insights aren’t that interesting in themselves, but the way he frames them are, even if they’re usually soaked in copious amounts of blood. His handling of colour and images is vastly more impressive second time around; the Alchemist’s room is like something imagined by Dali or Bunuel. ‘El Topo’ is a surreal riff on the Western genre, but goes on too long. The final episode makes sense of the mole proverb which gives the film its title, and works pretty well on its own, but hardly seems to connect with the rest of the film. Both films are unique experiences; expect to feel a little disorientated afterwards. I assure you that you’ll have never seen anything like this before, and you probably won’t again.