“The most beautiful land human eyes have ever seen” (

“The most beautiful land human eyes have ever seen” (The third episode begins with a firebomb at a drive-in. One of the participants, Enrique then rescues a local girl from being harassed by a group of drunk and rowdy American sailors. Newspaper reports, which we take to be pro-Batista propaganda report of the death of Castro, though his supporters know this isn’t true. Enrique is part of a group of pro-revolutionary students, who is instructed to assassinate a police chief, though he is unable to go through with this mission when he sees the man with his children. When the police raid the students’ headquarters, they find revolutionary literature, which one student throws out of the window, dispensing it to the students below. He is shot as he does this, and falls out of the window. This causes the students to mobilise and rebel against the police. Holding a dove (to symbolise peace, thus placing the blame squarely on the police), he leads the students who follow and sing songs of freedom. Though he is shot by the police chief he failed to assassinate, Enrique becomes a martyr and rallying point, and is afforded an elaborate parade and funeral.

The final segment focuses on Castro himself, hiding out in the hills and chased by Batista’s soldiers. He is one of numerous guerrillas on the run from the authorities. He is given refuge by a farmer who does not sympathise with Castro, and certainly refuses to fight alongside him. Castro then reinforces to the farmer how the current regime has let ordinary Cubans down and how things might improve. Castro mentions that the land the farmer works on is not his, that there are no schools or healthcare, and that there is widespread poverty. After Castro leaves, the village is bombed. The farmer and his wife are separated, as are their children; one of which dies during an explosion. The farmer then agrees to join the rebels and prepares for armed combat. ‘I Am Cuba’ then concludes with the rebels presumably marching to victory whilst stirring music accompanies their advance.

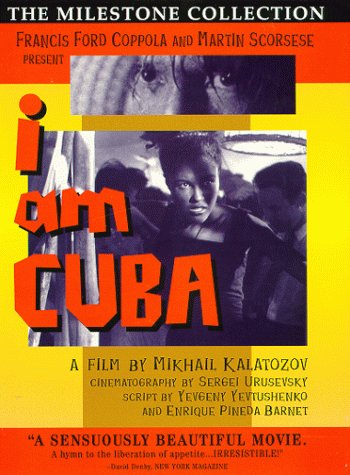

Whilst it’s partial treatment of life under the Batista regime and it’s looking forward to life for all improving under Castro (let’s remember that it was made just a few years after the Castro regime was established), one’s ideological preferences might indicate the extent to which one might appreciate ‘I Am Cuba’, but regardless of ideology, there is plenty to consider from a technical viewpoint. Not only is there the elaborate single take shot from the hotel to the pool in the first segment, but the camera always moves intricately as it documents events, giving it a documentary feel. There is also the stunning monochrome cinematography, with the Cuban streets during the Enrique segment being filmed in brilliant white. Although some of the promises the film suggests that Castro will deliver on were wide of the mark, the corruption of the previous regime and the impact of