The first film I reviewed for this blog was 'Mother Joan of the Angels' by this director, a stunning account of religious madness and sexual hysteria. His preceding feature, Night Train, is a superbly taut thriller, constantly challenging its audience about the identity of a murderer. Jerzy (Leon Miemczyk), in shades and a suit, boards a train bound for the Baltic coast. He's lost his ticket, but offers to purchase a two person sleeping car entirely for himself so he isn't disturbed. However his compartment is already inhabited by Marta (Lucyna Winnicka), who refuses to leave. Not wanting to make a fuss, Jerzy agrees to share the car. Both are ill at ease, don't wish to speak and act very suspiciously. Jerzy is then pursued by a married woman, who follows him when he goes to a tobacconists at a brief stop, whilst Marta is being chased by her ex-lover Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski), who acts as if he might explode at any moment. However, the train's passengers soon become alarmed by news that a murderer is on the loose in the area, and even more so when police suspect the murderer may be on the train. Suspicion then falls upon the private Jerzy.

The first film I reviewed for this blog was 'Mother Joan of the Angels' by this director, a stunning account of religious madness and sexual hysteria. His preceding feature, Night Train, is a superbly taut thriller, constantly challenging its audience about the identity of a murderer. Jerzy (Leon Miemczyk), in shades and a suit, boards a train bound for the Baltic coast. He's lost his ticket, but offers to purchase a two person sleeping car entirely for himself so he isn't disturbed. However his compartment is already inhabited by Marta (Lucyna Winnicka), who refuses to leave. Not wanting to make a fuss, Jerzy agrees to share the car. Both are ill at ease, don't wish to speak and act very suspiciously. Jerzy is then pursued by a married woman, who follows him when he goes to a tobacconists at a brief stop, whilst Marta is being chased by her ex-lover Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski), who acts as if he might explode at any moment. However, the train's passengers soon become alarmed by news that a murderer is on the loose in the area, and even more so when police suspect the murderer may be on the train. Suspicion then falls upon the private Jerzy. Monday 29 October 2007

Night Train (1959, Poland, Jerzy Kawalerowicz)

The first film I reviewed for this blog was 'Mother Joan of the Angels' by this director, a stunning account of religious madness and sexual hysteria. His preceding feature, Night Train, is a superbly taut thriller, constantly challenging its audience about the identity of a murderer. Jerzy (Leon Miemczyk), in shades and a suit, boards a train bound for the Baltic coast. He's lost his ticket, but offers to purchase a two person sleeping car entirely for himself so he isn't disturbed. However his compartment is already inhabited by Marta (Lucyna Winnicka), who refuses to leave. Not wanting to make a fuss, Jerzy agrees to share the car. Both are ill at ease, don't wish to speak and act very suspiciously. Jerzy is then pursued by a married woman, who follows him when he goes to a tobacconists at a brief stop, whilst Marta is being chased by her ex-lover Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski), who acts as if he might explode at any moment. However, the train's passengers soon become alarmed by news that a murderer is on the loose in the area, and even more so when police suspect the murderer may be on the train. Suspicion then falls upon the private Jerzy.

The first film I reviewed for this blog was 'Mother Joan of the Angels' by this director, a stunning account of religious madness and sexual hysteria. His preceding feature, Night Train, is a superbly taut thriller, constantly challenging its audience about the identity of a murderer. Jerzy (Leon Miemczyk), in shades and a suit, boards a train bound for the Baltic coast. He's lost his ticket, but offers to purchase a two person sleeping car entirely for himself so he isn't disturbed. However his compartment is already inhabited by Marta (Lucyna Winnicka), who refuses to leave. Not wanting to make a fuss, Jerzy agrees to share the car. Both are ill at ease, don't wish to speak and act very suspiciously. Jerzy is then pursued by a married woman, who follows him when he goes to a tobacconists at a brief stop, whilst Marta is being chased by her ex-lover Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski), who acts as if he might explode at any moment. However, the train's passengers soon become alarmed by news that a murderer is on the loose in the area, and even more so when police suspect the murderer may be on the train. Suspicion then falls upon the private Jerzy. Alexandra (2007, France/Russia, Alexander Sokurov)

Sokurov's new film begins with the eponymous woman (Galina Vishnevskaya) alighting a bus, then boarding an unnamed train, which is heading to an army camp in an unnamed region, though we imagine this to be Chechnya. Given the mutual enmity and contempt felt between Russians and Chechens, how has Sokurov managed to create such a dreamlike and striking film about their relationship - by concentrating on the human angle of course.

Sokurov's new film begins with the eponymous woman (Galina Vishnevskaya) alighting a bus, then boarding an unnamed train, which is heading to an army camp in an unnamed region, though we imagine this to be Chechnya. Given the mutual enmity and contempt felt between Russians and Chechens, how has Sokurov managed to create such a dreamlike and striking film about their relationship - by concentrating on the human angle of course.Wednesday 24 October 2007

Lust, Caution (2007, USA/China/Taiwan/Hong Kong, Ang Lee)

After the commerical and critical success of 'Brokeback Mountain' (2005), Ang Lee has taken a slight misstep with 'Lust Caution', his first Chinese feature since 'Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon' (2000). It has already achieved a degree of notoriety pre-release because of the NC-17 rating it has been awarded (which basically means box office death in the US, but what hope would a small budget Chinese picture have, even if it is directed by Lee) for explicit sexuality. This might paradoxically give it a sense of commercial longevity, especially given the anticipation to its showing at the London Film Festival, as well as press coverage, so maybe it's not going to be a total write off, despite the lukewarm reviews received thus far.

After the commerical and critical success of 'Brokeback Mountain' (2005), Ang Lee has taken a slight misstep with 'Lust Caution', his first Chinese feature since 'Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon' (2000). It has already achieved a degree of notoriety pre-release because of the NC-17 rating it has been awarded (which basically means box office death in the US, but what hope would a small budget Chinese picture have, even if it is directed by Lee) for explicit sexuality. This might paradoxically give it a sense of commercial longevity, especially given the anticipation to its showing at the London Film Festival, as well as press coverage, so maybe it's not going to be a total write off, despite the lukewarm reviews received thus far.Tuesday 23 October 2007

Funny Games (2008, UK/USA/France, Michael Haneke)

Given it's world premiere at the London Film Festival, Haneke's remake of his own 1997 masterpiece is bound to be divisive on release next year. Several critics have alresdy expressed bewilderment at Haneke's decision to embark on a remake of one of his early films, though he (and his producers) have justified it due to the fact that the original has barely been seen by an American audience (the box office receipts for the original amount to approximately $6000) and that Haneke always envisioned 'Funny Games' as an American film. Given the success of 2005's 'Hidden' (nearly £1m at the UK box office and just over $3.5 million at the US box office), Haneke now has the clout to remake his film and dictate his terms. Given the failures of compromised remakes like 'The Vanishing', perhaps it's best to allow directors to remake their films as they wish.

Given it's world premiere at the London Film Festival, Haneke's remake of his own 1997 masterpiece is bound to be divisive on release next year. Several critics have alresdy expressed bewilderment at Haneke's decision to embark on a remake of one of his early films, though he (and his producers) have justified it due to the fact that the original has barely been seen by an American audience (the box office receipts for the original amount to approximately $6000) and that Haneke always envisioned 'Funny Games' as an American film. Given the success of 2005's 'Hidden' (nearly £1m at the UK box office and just over $3.5 million at the US box office), Haneke now has the clout to remake his film and dictate his terms. Given the failures of compromised remakes like 'The Vanishing', perhaps it's best to allow directors to remake their films as they wish.Four Months Three Weeks and Two Days (2007, Romania, Christian Mungiu)

Who would have thought a few years ago that Romania would become a hotbed of film making talent? The first film to break through was 2005's 'The Death of Mr Lazarescu', which managed to secure a UK release on the arthouse circuit. Subsequent releases to critical acclaim have included 'California Dreamin' (also playing at the London Film Festival) and '12:08 East of Bucharest'. Further proof of a film making renaissance in Romania was at Cannes this year when 'Four Months Three Weeks and Two Days' won the Palme D'Or, which secured it a gala screening at this year's London Film Festival. Whilst there was some critical contention regarding whether the film deserved the main prize at Cannes, I'm pretty sure that none of the other nominees could match this film for sheer power and emotional impact.

Who would have thought a few years ago that Romania would become a hotbed of film making talent? The first film to break through was 2005's 'The Death of Mr Lazarescu', which managed to secure a UK release on the arthouse circuit. Subsequent releases to critical acclaim have included 'California Dreamin' (also playing at the London Film Festival) and '12:08 East of Bucharest'. Further proof of a film making renaissance in Romania was at Cannes this year when 'Four Months Three Weeks and Two Days' won the Palme D'Or, which secured it a gala screening at this year's London Film Festival. Whilst there was some critical contention regarding whether the film deserved the main prize at Cannes, I'm pretty sure that none of the other nominees could match this film for sheer power and emotional impact.Set in 1987 during the final years of Ceausescu regime, Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) is a student who finds herself pregnant in a country where abortion is illegal. Assisted by her friend Otilia (Anamaria Marinca), Gabita seeks an illegal abortion. Mungiu then demonstrates, in great detail, the lengths that desperate women would have to go to in order to achieve this. First of all, there's the issue of finding a large sum of money, which is borrowed with great difficulty. Then there's the booking of a hotel room under false pretences, and then finding someone willing to perform the procedure (Mr Pepe, a shady individual demands sex from Otilia when the pair cannot deliver all the money, and even then he explains it might not work); all of which needs to be achieved without raising the suspicions of the authorities. The consequences of being uncovered would be dire for all. The attention to detail of all these events can only make us sympathetic to the cause of the two women, but never maniuplates us emotionally. Abortion wouldn't be something entered into lightly, and the sacrifices that need to be made by both women are numerous. Mungiu never flinches from showing us the reality of the situation.

The lengths gone to in order to ensure the abortion is achieved has a natural impact upon the relationship between the women - both have to lie to each other, and Otilia has to lie to her boyfriend and jeapordise her relationship with him in order to keep the abortion secret. It's interesting that Mungiu places his focus not on Gabita, but Otilia, who does all the running to make the abortion possible and also to cover it up afterwards, including disposing of the dead foetus. She makes the ultimate sacrifices for her friend's benefit, and one wonders whether their relationship is salvagable by the film's climax.

Put simply, this is possibly the most impressive film of the year and deserves all the plaudits and prizes it will achieve. Mungiu remains sympathetic to the two main protagonists, but he never makes overt and simple political points which would be all too easy to lapse into. The film is immersed in the kind of tension that is unbearable and nerve shattering at all times, as the procedures that need to be undertaken could at any time arouse suspicion and land the two women in the kind of trouble that isn't worth thinking about. Marinca, given the most demanding role, delivers an absolutely wonderful performance - it's hard to see where you'll see anything better this year. 'Four Months Three Weeks and Two Days' really is faultless, and whilst I'm reluctant to throw around adjectives like 'masterpiece' just yet, there's every chance it will be seen as one of the key films of the decade in years to come.

Flight of the Red Balloon (2007, France, Hou Hsiao-Hsien)

The film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum once described Hou Hsiao-Hsien as one of the two most important film makers in the world at the turn of this century (Abbas Kiarostami being the second). His previous film, 2005's 'Three Times referred back to three of the films Hou directed in the 1990s (Goodbye, Goodbye South, The Flowers of Shanghai and Millennium Mambo), and distilled all the themes he's examined throughout his career. With this mind, one might reasonably argue that Hou had revisited past glories and needed to pursue new projects (not that Three Times wasn't anything other than great itself).

The film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum once described Hou Hsiao-Hsien as one of the two most important film makers in the world at the turn of this century (Abbas Kiarostami being the second). His previous film, 2005's 'Three Times referred back to three of the films Hou directed in the 1990s (Goodbye, Goodbye South, The Flowers of Shanghai and Millennium Mambo), and distilled all the themes he's examined throughout his career. With this mind, one might reasonably argue that Hou had revisited past glories and needed to pursue new projects (not that Three Times wasn't anything other than great itself).'Flight of the Red Balloon' is the first film that Hou has made in France, and is both inspired by and a homage to the classic 1956 short 'The Red Balloon' by Albert Lamorisse. Indeed the film begins with a red balloon mysteriously following a young boy, Simon (Simon Iteanu), as he rides the Metro. His mother Suzanne (Juliette Binoche) has just hired a new child minder named Song (Fang Song), and it is the relationship between Simon and Song that features more so than his relationship with Suzanne. Simon's father is absent and working on a book in Montreal, whilst Suzanne has enough problems of her own besides the lack of a husband; tenants who don't pay the rent, she's always rushed off her feet, and a job as a puppeteer that keeps her away from home (recalling Hou's own 1993 film), all of which affects her own emotional balance. Where is the support she needs?

Song potentially acts as Hou's alter ego in this sense; a foreigner from the Chinese diaspora observing Paris with the eye of an outsider. A student film maker, she is making a film that features red balloons, and she makes reference to the Lamorisse film in the early proceedings. What do we interpret about the motif of the red balloon; what does it represent? Song's caling influence upon the torn family? Is it anything more than in the imagination of those who see it? Hou avoids giving simple explanations and allows the viewer to interpret the imagery of the balloon.

One wonders whether Hou's ambitions are now aimed towards European film making, though IMDB reports that his next film is a Taiwanese thriller about an 8th century assassin reuniting the actors from 'Three Times' (Chen Chang and Qi Shu). As he seems to have reached a natural conclusion with his domestic film making with 'Three Times', it will be interesting to see how his career develops.

Monday 22 October 2007

Eastern Promises (2007, UK/Canada/US, David Cronenberg)

Eastern Promises opened the London Film Festival (I saw the second screening) and is the first Cronenberg film to be filmed entirely outside of his native Canada. The film has aroused much discussion already; perhaps not for the level of violence (exceptionally brutal), but mostly for the fact that Viggo Mortensen (developing quite the creative relationship with the director) is seen in all his glory in an public bath house.

Eastern Promises opened the London Film Festival (I saw the second screening) and is the first Cronenberg film to be filmed entirely outside of his native Canada. The film has aroused much discussion already; perhaps not for the level of violence (exceptionally brutal), but mostly for the fact that Viggo Mortensen (developing quite the creative relationship with the director) is seen in all his glory in an public bath house.Once (2006, Ireland, John Carney)

How does a romantic comedy that cost approximately £70,000 to film make $10 million and counting at the US box office? Simple. Follow the conventions of the genre, but do in a way that feels original and fresh. John Carney, an ex-bassist in Irish band The Frames directs his former bandmate Glen Hansard and Czech newcomer Marketa Irglova in this Dublin-set tale of boy meets girl (Carney states that the setting of Dublin is that of around 15 years ago when it had more of a working class feel to it). The unnamed characters randomly meet one day when he is busking and she is working one of her numerous jobs that she has to undertake in order to support her family, who are recent immigrants. She too has musical talent, and impresses him with a recital of a piece by Mendelssohn, which leads him to ask her to add piano to one of his own songs "Falling Slowly".

How does a romantic comedy that cost approximately £70,000 to film make $10 million and counting at the US box office? Simple. Follow the conventions of the genre, but do in a way that feels original and fresh. John Carney, an ex-bassist in Irish band The Frames directs his former bandmate Glen Hansard and Czech newcomer Marketa Irglova in this Dublin-set tale of boy meets girl (Carney states that the setting of Dublin is that of around 15 years ago when it had more of a working class feel to it). The unnamed characters randomly meet one day when he is busking and she is working one of her numerous jobs that she has to undertake in order to support her family, who are recent immigrants. She too has musical talent, and impresses him with a recital of a piece by Mendelssohn, which leads him to ask her to add piano to one of his own songs "Falling Slowly".Their musical collaboration mirrors their budding relationship, though they both have problems of the heart that get in the way. He's considering moving to England to win back his ex-girlfriend, whilst she has a husband back in the Czech Republic. When he asks whether she still loves him, she replies in unsubtitled Czech, though we instinctively know what she says. Still, Carney refuses to make the path of true love simple and doesn't rely on the kind of contrived slush that most films of the genre would fall back upon.

Much of Once's appeal depends on whether you love the music or not, which kind of falls into the kind of coffee table folk practiced by the likes of Damien Rice, though not quite as bland. It's not normally my thing, but works in context really well, but it might understandably be a hurdle for some. Still, the film was done wonders for the profile of The Frames, even drawing the attention of Bob Dylan who offered them a support slot on his latest tour. Some cynics see this as nothing more than a promo for the band. I don't know about that. There's certainly a sense of something about this film; maybe it's the fact that a no-budget film has succeeded in the US, maybe it's the fact that music is a core part of the film and not window dressing - that it actually drives the narrative, but moreover it works on an emotional level for me, which few, if any contemporary romantic comedies ever could.

Monday 8 October 2007

Control (2007, UK/USA, Anton Corbijn)

Not that there's anything obviously wrong with the film or anything. You couldn't fault the efforts of the acting personnel in any way at all; both Sam Riley and Samantha Morton as Ian and Deborah Curtis perform sterling work, and most of the supporting actors are more than adequate. Corbijn uses black and white to perfectly catch the period in which Joy Division emerged from - Macclesfield, a small town outside Manchester during the 70s, just prior to the explosion of punk.

Maybe the opening half an hour that concentrates of the teenage Curtis seems a little unnecessary beyond showing Ian meeting Deborah for the first time, and their teenage relationship that quickly became a marriage and family. Watching Corbijn longingly focus his camera on the semi-naked Curtis, listening to Bowie, Reed and Iggy Pop and reading Crash, The Naked Lunch and Howl (yeah, he's cool, we get it) just grates a bit after the first instance.

Curtis never appears to be too interested in keeping a balance between harmonious domesticity and his band (he's mean towards Deborah even before his lover Annik arrives on the scene, and he's nothing like a doting father on this evidence), so perhaps we should applaud Corbijn for not mythologising Curtis too much and presenting him as he really was. The steady rise of Joy Division around 1979-1980 coincided with Curtis developing epilepsy; the pressures of which eventually told as his condition was always going to affect the band (several gigs were abandoned during his horrifyingly recreated seizures) and his marriage. Falling in love with Annik, a glamorous Belgian wasn't able to make Curtis happy as he still felt bound to Deborah and was unable to make a final break with her. Eventually the mounting pressure told. Curtis delivers a soliloquoy admitting his weaknesses, that he's given all he can possibly give and yet people still ask him for more, which asks questions about the future of Joy Division had he lived - would he have still wanted the band to be successful and all the trappings that go with it. As we know, he didn't.

Corbijn films Curtis' decline as sympathetically as he possibly can without making him look too glamorous. We never really get to know too much about his relationship with Annik, which isn't surprising as the film is based on Deborah Curtis' book, and I'm not sure whether the mistress was involved in the production in any way. What was private between them presumably still remains so, so her character isn't fleshed out so much, and we never know whether they were happy, so maybe that's a valid shortcoming of the film - that you don't get the whole story, just what is known.

Control really succeeds in the recreation of Joy Division's music though. The actors playing Stephen Morris, Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook are all talented musicians in their own right, and with Sam Riley, they play Joy Division's music rather than rely on miming with backing tapes, and it works so much better for doing so. It evokes what it must have been like so much more, and also reminds you that live they sound so much louder and primal than they did on record, which was partly because of the excellent production job that Martin Hannett achieved on their records. It's then that the film comes alive. The fact that it doesn't always do so makes Control something of an uneven film. Maybe it's too reverential who knows; that the people involved want to do Ian justice so much that the film never feels alive.

Dead of Night (1945, UK, Alberto Cavalcanti et al)

Dead of Night is a superior horror film from Ealing Studios, best known for its whimsical comedies. Invited to a country house, an architect believes he recognises all of the other guests from a surreal and recurring dream. The other guests then all tell nightmarish tales they have experienced or heard (a racing driver who avoids death, a dead boy seen during a hide and seek game, a man who is possessed by the reflections he sees in a mirror, a jovial tale of golfers fighting over the same woman, and a ventriloquist and his dummy whose personas are inextricably linked).

Dead of Night is a superior horror film from Ealing Studios, best known for its whimsical comedies. Invited to a country house, an architect believes he recognises all of the other guests from a surreal and recurring dream. The other guests then all tell nightmarish tales they have experienced or heard (a racing driver who avoids death, a dead boy seen during a hide and seek game, a man who is possessed by the reflections he sees in a mirror, a jovial tale of golfers fighting over the same woman, and a ventriloquist and his dummy whose personas are inextricably linked).The Hole (1998, Taiwan/France, Tsai Ming Liang)

At the end of the millennium Taipei is overwhelmed by an epidemic that the government cannot contain, and the rain is torrential and endless. Whilst most people are evacuated, in an anonymous tower block two residents stay around. The potential for connection is both metaphorically and physically created by a plumber's poor workmanship which creates a hole in the floor/ceiling which separates their apartments. The unnamed male and female protagonists go on with their lives as best they can in a pretty unpopulated city where food and provisions are scarce, but they sometimes meet, which then turns 'The Hole' into a surreal musical. In glorious colour, Tsai Ming Liang portrays her state of mind through stunningly choreographed song and dance routines where the woman believes she is Grace Chang, a Taiwanese pop singer from the 1950s and 1960s, and croons her way through several cabaret style songs of love and longing, which is in stark contrast to the dire situation she finds herself currently in.

At the end of the millennium Taipei is overwhelmed by an epidemic that the government cannot contain, and the rain is torrential and endless. Whilst most people are evacuated, in an anonymous tower block two residents stay around. The potential for connection is both metaphorically and physically created by a plumber's poor workmanship which creates a hole in the floor/ceiling which separates their apartments. The unnamed male and female protagonists go on with their lives as best they can in a pretty unpopulated city where food and provisions are scarce, but they sometimes meet, which then turns 'The Hole' into a surreal musical. In glorious colour, Tsai Ming Liang portrays her state of mind through stunningly choreographed song and dance routines where the woman believes she is Grace Chang, a Taiwanese pop singer from the 1950s and 1960s, and croons her way through several cabaret style songs of love and longing, which is in stark contrast to the dire situation she finds herself currently in.Back in reality though, the protagonists try to stick with their routines; hers involves the odd stockpiling of toilet roll and he sticks to voyeurism. The prevailing theme in Tsai Ming Liang's films is the need for connection and the inability for individuals to achieve it in the modern world (maybe he's the heir to Antonioni in that respect), and these individuals struggle with their need to make contact with each other, though the final scene finds the man and woman finally doing so, which begins one final musical fantasy. Tsai Ming Liang's film may be as much about Grace Chang as it is these individuals. He closes with a respectful acknowledgement towards her music and the joy it brought him, as much as it did for the female protagonist of The Hole.

Thursday 4 October 2007

The Ear (1970, Czechoslovakia, Karel Kachyna)

Like most of the films that were made during the burst of film making creativity in the late 60s in the former Czechoslovakia, The Ear was banned - the authorities took a disliking to the open criticising of the methods employed by the secret police to spy on its own government officials.

Like most of the films that were made during the burst of film making creativity in the late 60s in the former Czechoslovakia, The Ear was banned - the authorities took a disliking to the open criticising of the methods employed by the secret police to spy on its own government officials.Thinking over events at the party, Ludvik begins to wonder whether he is under surveillance by the state, like a recent colleague who has since been arrested. He disposes of anything incriminating (which blocks the toilet) and takes care with what he says, partially drowning his conversations with Anna with the radio, though she doesn't share Ludvik's suspicions until she seens men furtively wandering in the gardens.

When the power returns and a number of men appear at the gate, frantically ringing, both assume Ludvik is about to be taken away, though it emerges that these men are friends of his from the party. Anna's paranoia outstrips Ludvik's, who at least superficially seems calm and reassured, though this is probably a facade whilst he tries to figure out what's going on. By the morning however, all becomes clear of the purpose of these men. For the rest of the evening, Ludvik and Anna project their fears onto each other and become totally frank about their loathing for one another in order to hurt the other - Anna taunts Ludvik with her history of promiscuity, whilst he tells her he was only interested in her money. However, when they find bugging devices all over their home (planted by their guests), this almost solidifies their marriage as they have to work together to save themselves. In a blackly comic denouement, Ludvik is promoted to replace Kosara, his friend who was recently arrested, though the future is somewhat indeterminate.

Monday 24 September 2007

The Eclipse (Italy/France, 1962), Michelangelo Antonioni and The Red Desert (Italy/France, 1964, Michelangelo Antonioni)

A double bill of early Antonioni films that focus on the alienation of modern industrial societies, both featuring the glamourous (and gorgeous) Monica Vitti. The Eclipse forms the third part of a trilogy with L'Avventura and La Notte, both of which I've yet to see, whilst The Red Desert seems to further develop the themes from these films, although Antonioni uses colour and sound more prominently to emphasis the alienation of his protagonists.

The Eclipse begins with an agonising and drawn out break up. It's several minutes before any meaningful dialogue; the silences speak more than the actual individuals involved ever could. Vittoria (as played by Vitti) is by her own admission "tired, depressed, disgusted and disorientated". When meeting her feckless mother who gambles daily at the stock exchange, she meets Piero, a stockbroker (played by Alain Delon), who pursues her, even though she rejects his advances. To Vittoria, love is a great effort. Piero on the other hand is ruthlessly materialistic and successful; witness the exceptional replication of the goings on at the Rome stock exchange where he thrives. He too is insensitive - when a drunk steals his car and drives it into the river, he is more concerned about the car than the fate of the dead man. He represents the vitality of capitalism; the source perhaps of contemporary human alienation, and her romantic and brooding personality so at odds with his dooms their future - she is unable to love or know him, so she chooses to be alone rather than marry him.

The Red Desert is thematically quite similar. Vitti is Giuliana, a wife recovering from a car accident, who finds no understanding from her husband and finds herself unsettled in her environment. Using colour for the first time, Antonioni is able to amplify this sense of alienation through the unique palette he employs (the reds in particular are very striking in colour), as well as the electronic soundtrack he uses, which is incredibly disorientating, thus reflecting Giuliana's state of mind. The bleak landscape of Ravenna (heavily industrialised and polluted) adds further emphasis to her sense of dislocation. Giuliana's husband's behaviour encourages her to consider an affair with an engineer played by Richard Harris, who seems more sympathetic to her neurotic condition than her husband.

The Red Desert to a degree concludes Antonioni's examination of alienation and loneliness in the modern world. Both films are emotionally devastating pieces of work, held together by the phenomenal performances given by Monica Vitti. Whereas The Red Desert is probably the more ambitious of these films, it does feel like the less involving, though maybe that's the point. Much time and patience has to be invested in these films in order to get the most out of them as events in them often appear pretty random, but all form part of a studied examination of the malaise of both characters that Vitti plays. Antonioni's films have tended to be pretty divisive critically, and these are no exceptions. They will baffle as much as they will entrance.

Friday 21 September 2007

The Painted Veil (US, 2006, John Curran)

Adapting classic texts is always a tricky proposition and often a gamble. Just consider how The Bonfire of the Vanities and the numerous versions of The Great Gatsby turned out. Such is the weight of expectation, as well as the fact that film makers have to respect the original work, perhaps it's no wonder that it sometimes goes wrong. As the Maugham novel is one of my favourites, I felt a degree of concern at how the novel would be treated. John Curran and Ron Nyswaner, the screenwriter has remained pretty faithful to the novel, though I'm pretty of the opinion they overdeveloped the love that Kitty begins to feel for Walter after years of a loveless marriage (there was nothing like the later passion in the book). There's shifts in chronology too - the 'England' scenes are shown entirely in flashback and it feels like they're rushed through (even though this is a two hour film!). Because of this, the film loses some of its context.

Adapting classic texts is always a tricky proposition and often a gamble. Just consider how The Bonfire of the Vanities and the numerous versions of The Great Gatsby turned out. Such is the weight of expectation, as well as the fact that film makers have to respect the original work, perhaps it's no wonder that it sometimes goes wrong. As the Maugham novel is one of my favourites, I felt a degree of concern at how the novel would be treated. John Curran and Ron Nyswaner, the screenwriter has remained pretty faithful to the novel, though I'm pretty of the opinion they overdeveloped the love that Kitty begins to feel for Walter after years of a loveless marriage (there was nothing like the later passion in the book). There's shifts in chronology too - the 'England' scenes are shown entirely in flashback and it feels like they're rushed through (even though this is a two hour film!). Because of this, the film loses some of its context.Thursday 20 September 2007

The Cranes Are Flying (Soviet Union, 1957, Mikhail Kalatozov)

Made almost as soon as the Krushchev Thaw was introduced in 1956, when repression and censorship was slightly reversed, The Cranes are Flying is one of the first films from the Soviet Union to swerve from the accepted policy of near glamourising The Great Patriotic War (1941-1945 of the Second World War). It's unthinkable that this film might have been made in this way just years before, as no doubt the demands to produce patriotic propaganda would have been too great.

Made almost as soon as the Krushchev Thaw was introduced in 1956, when repression and censorship was slightly reversed, The Cranes are Flying is one of the first films from the Soviet Union to swerve from the accepted policy of near glamourising The Great Patriotic War (1941-1945 of the Second World War). It's unthinkable that this film might have been made in this way just years before, as no doubt the demands to produce patriotic propaganda would have been too great.Sunday 19 August 2007

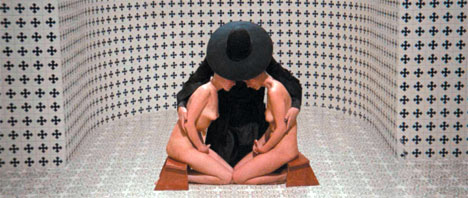

Persona (Sweden, 1966, Ingmar Bergman)

The film world sadly lost two of its greats on 30 July this year, when Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman passed away. Having already reviewed Antonioni’s ‘Professione: Reporter’ (and won’t someone finally release his classic early 60s films on DVD?), I thought it was time Bergman received the same treatment. Shamefully to this point I have only seen a few of his films, from the great ‘Cries and Whispers’ to the less great ‘From the Life of Marionettes’. Persona certainly resides with the greats and compares favourably with them.

The film world sadly lost two of its greats on 30 July this year, when Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman passed away. Having already reviewed Antonioni’s ‘Professione: Reporter’ (and won’t someone finally release his classic early 60s films on DVD?), I thought it was time Bergman received the same treatment. Shamefully to this point I have only seen a few of his films, from the great ‘Cries and Whispers’ to the less great ‘From the Life of Marionettes’. Persona certainly resides with the greats and compares favourably with them.Much can be interpreted from Bergman’s use of interludes of clips from films, which some have cited as a Brechtian alienation technique. The film begins with several clips, which includes crucifixion, a dead sheep, a cartoon, a spider (which Bergman uses as a symbol to represent God elsewhere) and notably a boy whose mother’s face is projected, distorted, on a screen (which I’m sure is meant to be Elizabet’s son). In some school of psychological thought, these represent childhood images of trauma, but it also represents an indication of the fictional and artificial nature of the film on Bergman’s part.

Tuesday 14 August 2007

Devi (India, 1961, Satyajit Ray)

One of the first post-Apu films of Ray’s career takes as its main themes religious obsession and superstition. The opening titles refer to Kali, a revered deity, who is then worshipped during an elaborate ceremony by the community of a small Indian village. Rumour has it that Kali is sometimes reincarnated in human form, a belief which is taken most seriously by the old and infirm Kalikinkar. When his son, Uma, leaves to study in Calcutta, he becomes reliant on his daughter in law, Doya, whom he believes to be the goddess reincarnated after a feverish vision. Despite initial scepticism amongst some in the village, and even within the old man’s own family (his other daughter in law thinks it’s ridiculous, and is proclaimed jealous, whilst her husband seems to ‘believe’ just to please his father who favours his more academically minded son), such is the old man’s influence and authority within the village that many become convinced, especially when the Doya appears to perform miracles. A peasant brings his dying child to see her, whom she apparently cures.

One of the first post-Apu films of Ray’s career takes as its main themes religious obsession and superstition. The opening titles refer to Kali, a revered deity, who is then worshipped during an elaborate ceremony by the community of a small Indian village. Rumour has it that Kali is sometimes reincarnated in human form, a belief which is taken most seriously by the old and infirm Kalikinkar. When his son, Uma, leaves to study in Calcutta, he becomes reliant on his daughter in law, Doya, whom he believes to be the goddess reincarnated after a feverish vision. Despite initial scepticism amongst some in the village, and even within the old man’s own family (his other daughter in law thinks it’s ridiculous, and is proclaimed jealous, whilst her husband seems to ‘believe’ just to please his father who favours his more academically minded son), such is the old man’s influence and authority within the village that many become convinced, especially when the Doya appears to perform miracles. A peasant brings his dying child to see her, whom she apparently cures.Her husband believes the old man is out of his mind, and tries to take his Doya away from the village to Calcutta. However, she is now convinced that she is indeed Kali reincarnated, and refuses to leave with him. The true test of her divinity arises when her nephew, Khoka falls ill. His mother, unconvinced by the whole situation, refuses to take her son to see Doya. Her husband tells Kalikinkar, who then insists upon Doya curing the boy. Of course, tragedy strikes.

Doya’s husband, upon his return, is the only person who can make sense of what happened. Kalikinkar thinks the boy died because he was punished for his own sins. His son tells him he was responsible, because he didn’t send for a doctor to treat the boy. His faith was so blind that he thought Doya would save the boy’s life. Doya herself is stricken with grief having failed, and descends into madness.

Ever the humanist, Ray highlights the dangers of fanaticism and religious obsession, but approaches this with great subtlety and care, rather than a heavy-handed approach. Doya finds herself exploited by those more powerful than her, who project their beliefs upon her and strip her of her identity as well as jeopardise her marriage. These beliefs are held at the expense of rationality, and those who hold them most put at risk their own families in order to prove them. Yet Ray never strays into being too judgemental with these religious obsessives; he just presents them as being misguided, though this doesn’t prevent the tragedies which occur. Another splendid film by one of the greatest film makers of the twentieth century.

Days and Nights in the Forest (India, 1970, Satyajit Ray)

To commemorate sixty years of Indian independence, the Curzon cinema chain is showing a mini-season of films by India’s most famous and celebrated film maker, Satyajit Ray, which also includes his famous work, The Apu Trilogy. These following two films are much less known, but just as intriguing and remarkable.

To commemorate sixty years of Indian independence, the Curzon cinema chain is showing a mini-season of films by India’s most famous and celebrated film maker, Satyajit Ray, which also includes his famous work, The Apu Trilogy. These following two films are much less known, but just as intriguing and remarkable.Days and Nights in the Forest focuses on four men who are leaving Calcutta for a vacation in the countryside. They immediately strike us as vain and materialistic, and comfortable in their Western attitudes (which include references to Western popular culture, e.g. American western movies). With this apparent confidence goes a patronising attitude to their rural countrymen and a belief that they act as they wish without consequences. When told a guesthouse needs to be booked for them to stay there, they bribe the caretaker, despite the fact his job would be at risk (“thank God for corruption”). They hire a local boy to run errands and so on, and mistreat him, which comes back to haunt one of them later on. The men make a symbolic break with their lives in Calcutta though by burning the newspaper they had with them, though their values and mindsets are distinctly at odds from those of the rural folk. The men get drunk; try their luck with local ‘tribal women’ and make fools of themselves.

However, their vacation suddenly is spurred into action beyond simple leisure by the sight of two refined women, who are clearly more like the women of Calcutta, and they all try their hardest to impress them, although this generally ends with the men embarrassed or humiliated in some way, such as when the women catch them bathing by a well or when the men unwittingly flag their car in the middle of the road one night when drunk. Despite this, the women seem drawn to the men, partly because of their own frustrations in living in such a remote place with their father. Perhaps they yearn for the freedom and lifestyles these men enjoy back home. During a picnic, Rini (the youngest woman) and Ashim (the most dominant of the four men) play a memory game that has sexual undertones (similar to the famous chess game in ‘The Thomas Crown Affair’ perhaps). Sanjoy, the most serious of the four men, courts Jaya, though this is short lived once he discovers that she is the widow of a man who committed suicide. Hari, who was rejected by his lover back in Calcutta (his version of events differs from the flashback Ray presents) becomes fixated with Duli, a local girl, and seduces her in the woods, which incurs the wrath of the boy Hari mistreated earlier. The boy extracts revenge by attacking Hari and robbing him.

By the time the four agree to return to Calcutta, it’s interesting that Ray presents their confidence as being little more than superficial. As the film develops, their insecurities and fears about their jobs and their futures come to the fore, and they are finally able to admit and identify their shortcomings away from the competitive worlds they normally reside in, as if the countryside is a retreat away from their lives. The men are then presented more sensitively, and show themselves to be more complex than the arrogant city dwellers they appeared. Days and Nights in the Forest blends comedy and drama exceptionally well, and is so effortlessly handled by Ray. Time Out describes this film as his masterpiece, and perhaps few would disagree.

Monday 6 August 2007

The Lady from Musashino (Japan, 1951, Kenzo Mizoguchi)

The only previous Mizoguchi film I’ve seen is ‘Tale of the Late Chrysanthemums’, made more than a decade before, but both films demonstrate an interest in the themes that recurred throughout his career; notably the position of women in Japanese society and their subjugation and struggle. Set just outside Tokyo during the last days of World War Two (we can sense the bombing of the cities frequently), the film begins with a married couple (Michiko and Akiyama) returning to her parental home. Michiko is from an aristocratic family, whilst her husband is from peasant stock, which was naturally difficult from her family to accept. However, with Michiko as the now widowed father’s only child, it is imperative that they remain together and raise a family in order to keep the family going. Her father frequently reinforces this, and the responsibilities of this instruction cause Michiko great upset in the future.

The only previous Mizoguchi film I’ve seen is ‘Tale of the Late Chrysanthemums’, made more than a decade before, but both films demonstrate an interest in the themes that recurred throughout his career; notably the position of women in Japanese society and their subjugation and struggle. Set just outside Tokyo during the last days of World War Two (we can sense the bombing of the cities frequently), the film begins with a married couple (Michiko and Akiyama) returning to her parental home. Michiko is from an aristocratic family, whilst her husband is from peasant stock, which was naturally difficult from her family to accept. However, with Michiko as the now widowed father’s only child, it is imperative that they remain together and raise a family in order to keep the family going. Her father frequently reinforces this, and the responsibilities of this instruction cause Michiko great upset in the future.When Michiko’s father dies soon after the war, she inherits the family home and wealth, though it is this that encourages her cousin, Tsutomu, to return to the family home. He is set up as a complete opposite to Akiyama; he is sensitive and sympathetic, in comparison with Akiyama’s indifference. Akiyama seeks out affairs with other women, notably a friend of Michiko’s named Tomiko. His excuses are that she treats him like an outsider because he isn’t her social equal and is distant towards him, paying him no attention.

Akiyama’s distance brings Michiko and Tsutomu together, and a mutual love starts to develop. Whilst Tsutomu is open about declaring his feelings, Michiko is forced to restrain herself and not act upon hers. She is aware that by doing so, she would disgrace the family name, and is willing to sacrifice her own happiness in order to keep her family’s integrity. Forced to book a room in a hotel together during a torrential rain storm, Michiko fights Tsutomu off when he tries to make a move on her. Even though she knows Akiyama is behaving improperly, she tells Tsutomu that they must. Despite the fact that their relationship is completely chaste, this doesn’t stop Tomiko gossiping to Akiyama about what might be going on between his wife and her cousin, though this occurs after she is rejected by Tsutomu. Akiyana is typically self-righteous on this issue, requesting a divorce and setting Michiko up as the guilty party.

Tomiko and Akiyama run off together with the property deed to Michiko’s house. When told by a lawyer that the only way he can be thwarted is if Michiko changes her will, which she indeed does, placing Tsutomu as sole inheritor of her fortune when she commits suicide. She blames herself still, for provoking Akiyama into having an affair. As she dies, the remaining protagonists blame each other for what has happened, though Tomiko makes the pertinent point that “You men brought her to this”, an indictment of society as much as this group of individuals.

Though not considered as one of the supreme Mizoguchi films like ‘The Life of Oharu’ and ‘Sansho The Bailiff’, ‘The Lady from Musashino’ is still a superb melodrama that accurately portrays a Japan that is still in transition between old and modern values and which still reinforces paternalistic values at the expense of undermining the position of women in society. Michiko is a virtuous heroine, sacrificing herself for her family name and marriage to a feckless adulterer, and let down by everyone.

Friday 27 July 2007

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Japan, 1960, Mikio Naruse)

The BFI Southbank showed a retrospective of the shamefully overlooked Japanese director this July, of which this film was the focal point, and according to many, the high watermark of Naruse’s career. Most discussions about the early post-war Japanese cinema concentrate on the three directors known in the West; Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi. There is certainly no reason why on the basis of this masterpiece that Naruse should not be discussed in the same breath. Many of his other films which I’ve yet to see (‘Repast’, ‘Floating Clouds) are reportedly the equal of ‘When a Woman Ascends the Stairs’, yet very little of his output is available on DVD; just the three film box set at present, though perhaps this might change in the near future. Thematically, Naruse has much in common with Mizoguchi, concentrating on the position of women in Japanese society, their subjugation and mistreatment by men and his sympathy usually resides with those women on the margins of society, such as Mama San, the heroine of this film.

The BFI Southbank showed a retrospective of the shamefully overlooked Japanese director this July, of which this film was the focal point, and according to many, the high watermark of Naruse’s career. Most discussions about the early post-war Japanese cinema concentrate on the three directors known in the West; Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi. There is certainly no reason why on the basis of this masterpiece that Naruse should not be discussed in the same breath. Many of his other films which I’ve yet to see (‘Repast’, ‘Floating Clouds) are reportedly the equal of ‘When a Woman Ascends the Stairs’, yet very little of his output is available on DVD; just the three film box set at present, though perhaps this might change in the near future. Thematically, Naruse has much in common with Mizoguchi, concentrating on the position of women in Japanese society, their subjugation and mistreatment by men and his sympathy usually resides with those women on the margins of society, such as Mama San, the heroine of this film.A hostess approaching her thirtieth birthday, an age where women in her profession are considered past their sell by date, Mama San yearns to own her own bar, yet she’d require the patronage of a wealthy backer, which would be unlikely without prostituting herself. Yet Mama San is a dignified woman, far more refined and virtuous than some of her fellow hostesses. She frequently mentions that women should not be loose and that they lose their charm if they fool around. Despite the nature of her profession, Mama San aims for respectability; she hates the ascent she makes from the respectable street level life to the more sordid world of her work. Mama San is caught in a vicious circle she can’t leave; a widow since her husband was run over, she supports her feckless family as well as her own son. An impossible set of pressures to balance, Mama San makes a number of poor decisions thereafter, though never once loses the sympathy of the director.

Aware of the need to find a rich husband, she agrees to marry Sakine, an amiable large man, who is more respectful towards Mama San than many of her clients, even though she does not love her. Her nephew needs an operation to walk, but her act of self-sacrifice comes to nothing when she discovers that Sakine has a wife and has little money. Shattered, she starts to drink herself to death and becomes everything she vowed not to become, allowing herself to be seduced by Fujisaki, a man who loves her, but cannot bring himself to break up his family to be with her. Mama San’s manager who also loves her, is aware of this and informs her that he is disappointed in her and lost all respect for her. Mama San refuses to marry him, thus leaving her in the same position that she began the film, only compromised in her morals and in fear of being ‘past it’.

Like Mizoguchi, Naruse was a master at examining the role and position of women in Japanese society, though his interest was in more contemporary settings and environments than Mizoguchi, who approached these themes from a more historical perspective. Always sympathetic to his females, he presents the men on whom they depend as fickle and weak, always ready to betray and sacrifice them. The man Mama San loves is unattainable, yet keeps her at sufficient distance to give her hope, and the man she agrees to marry isn’t what he appears to be at all. The dashing of these dreams sends her into a downward spiral she doesn’t recover from. The unglamorous world of these late night bars are seen as traps that these women cannot remove themselves from; the potential riches derived from them are enticing enough to make women consider compromising themselves, and those not willing to totally give themselves to them are in danger of falling apart. A tragic, heartbreaking tearjerker.

Tuesday 3 July 2007

A Long Weekend in Pest and Buda (Hungary, 2003, Karoly Makk)

The collapse of Communism had a significant impact upon the fates of many of the gifted film makers from

The collapse of Communism had a significant impact upon the fates of many of the gifted film makers from Following this, Makk was able to make a sequel of sorts to his remarkable ‘Love’, made in 1971. The characters are now different; Luca has become Mari, and Janos has become Ivan, but the two actors more or less reprise their roles from ‘Love’. Flashbacks from ‘Love’ are used, and the husband was also arrested during the 1950s on political charges, so whilst it’s not a straight forward sequel so to speak, it’s not far off.

Mari and Ivan are no longer married, but they appear in each other’s lives once more when Ivan (now living in Lugano) receives a telephone call from Mari’s nurse, who explains to him that she is close to death and that if he is ever going to see her again, it has to be now. Ivan has a new life, a second wife, but returns to

Makk’s intentions are not to seek reconciliation between Mari and Ivan, whose marriage is well beyond them. However, when Ivan fled

Anna has her own issues though; an on-off relationship with a semi-legitimate businessman (another indication of the corrupt post-Communist world), so Ivan’s arrival only serves to complicate things further. Ivan shows her his place of birth and tells her of his childhood to connect with her, though this excursion has tragic consequences, when they both miss Mari’s death, which Anna blames him for. Rejected by her and with his ex-wife dead, Ivan returns to Lugano; his wife gone. The film closes with Anna calling her father; their relationship appears to be a permanent one, lasting beyond the death of the woman they had in common (similar to ‘Love’ in many ways).

Makk’s film would be a pretty successful venture in its own right, though it’s hard to be too objective watching it, as it’s going to naturally draw comparisons with ‘Love’, which I consider a masterpiece. The themes of ‘Love’ and the political conditions in which it was made and set aren’t so prevalent here. ‘A Long Weekend…’ is a film purely focused on reconnection between people, which is fine, but doesn’t have the same kind of depth its predecessor had. The comparison between Communist and post-Communist

Wednesday 13 June 2007

The Red and the White (Hungary/USSR, 1967, Miklos Jancso)

Many Hungarians joined the Russian cause because they thought that in the long run, it would benefit their own country, which faced an uncertain future when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dismantled by the peace settlements of 1919, and Hungary became an individual, self-governing nation. The question of course is, did it? Since Jancso shows the Reds in a none too sympathetic light, perhaps not. Many Russians were less than keen on Hungarian involvement; some Hungarians are told that they don’t want them fighting their war. In many ways, The Red and the White summarises and reinforces the often fraught relationship the two countries have endured over much of the twentieth century.

One could argue that Jancso films with a policy of detachment. The Reds and the Whites are never named and are often indistinguishable, there is little in the way of characterisation, and his main cinematographic preference is for long takes with very little camera movement, often from distance. It’s as if the director doesn’t want to get too close to his subjects or attempt to analyse or empathise with them. He prefers to depict events as they occur and have little more input beyond this. This approach allows him to be impartial and not sensationalise or over dramatise the numerous shocking acts of violence he films, such as massacres of entire towns, allowing enemies a few seconds head start to run before being picked off, and coldly shooting enemies right between the eyes indiscriminately. Despite much of this violence being committed by the Whites, Jancso affords some of the counter-revolutionaries a conscience and a degree of moral integrity. When one White soldier attempts to rape a woman in a small town, his officer orders him to be executed for his dishonour. This captures the peculiar mindset of men at war; that when faced with your enemies, anything goes. Yet those who are innocent and uninvolved should be treated with respect and dignity. It’s strange just to be able to turn on and off like that.

Where there is anything like a narrative, I suppose it exists as much as concentrating on a few Hungarian Reds trying to avoid the Whites and escape capture. The unlucky escapees commit suicide before being captured, whilst the fortunate either ambush the Whites, hide in lakes whilst they pass, or pretend to be wounded Whites at a nearby infirmary. The nurses explain that there are no “Reds or Whites here, only patients”, reinforcing that these are men with much in common, separated by ideology (though interestingly we never hear any indications of the ideologies of these forces or why they’re fighting). The Whites arrive and ask for the Reds and the Whites to be separated, though this coincides with a major fight back by the Reds, culminating in a glorious and sweeping shot from distance of the two armies marching towards each other (which cannot be told apart) at approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes into the film. This resolution is open ended, with no judgements of any kind, or any indication of how events might pan out. Jancso sees the whole futility of this exercise and closes with a march towards death, with the forces fighting for no other reason than to fight.

Saturday 9 June 2007

Szerelem (Hungary, 1971, Karoly Makk)

Karoly Makk is considered one of the best post-war Hungarian directors, and is certainly one of the best cinematic commentators of the Communist experience in Eastern Europe. ‘Szerelem’ (translated as ‘Love’) is his best received film, and finally gets a Western release thanks to the sterling work of Second Run, who are steadily carving out a niche for themselves as distributors of great, unknown films from largely ignored national cinemas. Based on two short stories written by Tibor Dery, Makk’s film nominally focuses on the love a wife (Luca) and a mother have for a man (Janos) whom we never see until the final quarter of the film, and the relationship between the two women.

Karoly Makk is considered one of the best post-war Hungarian directors, and is certainly one of the best cinematic commentators of the Communist experience in Eastern Europe. ‘Szerelem’ (translated as ‘Love’) is his best received film, and finally gets a Western release thanks to the sterling work of Second Run, who are steadily carving out a niche for themselves as distributors of great, unknown films from largely ignored national cinemas. Based on two short stories written by Tibor Dery, Makk’s film nominally focuses on the love a wife (Luca) and a mother have for a man (Janos) whom we never see until the final quarter of the film, and the relationship between the two women.‘Szerelem’ is set in 1953, when Hungary was under the totalitarian rule of Mátyás Rákosi during which thousands of real and imagined foes were killed or arrested. Janos has been arrested on an unknown, but presumed fictitious charge, and is serving a nine year sentence. Luca is not permitted to see her husband and knows not whether he is alive, let alone in good physical health. Janos’ mother is looked after by Luca and a housekeeper. A seriously ill, bed-ridden woman, she does not know what has happened to her son. Since she does not have long to live, and that the shock of Janos’ arrest might kill her, Luca constructs a web of deceit, writing letters supposedly from Janos that tell of his great success as a film director in the United States. These are very elaborate letters, written in great detail, that even the housekeeper claims are beyond the realm of probability. So why doesn’t Janos’ mother suspect that not all is as it seems to be? Luca tells the housekeeper that she is ‘deaf and blind’ when it comes to Janos. Such is her love for her son that she will believe any news of his supposed success.

However, there is one idea that she wants to believe what Luca’s letters present, and gives the impression to believes it wholesale, but that she has some idea of the truth. Much of the narrative is composed of the memories and thoughts of Janos’ mother. When reading the prose of the letters Lucas has written, Makk visually presents her thoughts and intrerpretations. When she talks to Luca about her past, this is presented through a series of flashbacks. In one instance of reading a latter, Makk presents a series of random thoughts, but these are interspersed with flashes of the prison cell that we later see Janos has been imprisoned in. Therefore, should we determine that the inclusion of these shots suggests that Janos’ mother suspects what he really happened to him, and that she is deluding herself somewhat when Luca paints a picture of his success abroad?

Aware of her impending death, the mother tells Luca she has to see Janos again, possibly a tactic designed to confront Luca and force the truth out of her, though the mother backs down with this request when Luca says he would have to leave the film he is currently working on. She never gets her wish however, as she contracts pneumonia and only survives a few days after it’s diagnosed. As soon as he passes, Janos is released from prison, and Makk then shifts focus to Janos’ own feelings of disorientation and uncertainty. During his spell in prison, much has changed and he finds difficulty in coping and returning to a home he has not been part of, and a wife he has barely seen in the last several years. However, their love binds them together and sustains their marriage (which we assume, considering Makk has directed a sequel of sorts ‘A Long Weekend in Pest and Buda’ (2003) and also with their mutual declaration of an undying love).

For a film that is set during the most dangerous point in recent Hungarian history, and focuses on a man’s false imprisonment, Makk’s film is surprisingly lacking in political insight and bite. We don’t find out what Janos was arrested for, and the sole government officials we see are those overseeing his release, and possibly two men who claim to be from the telephone exchange. This is deliberate of course; partly because it was still filmed under Communism (albeit an era that had moved on from the terror of the Rákosi regime), but also because Makk obviously wishes to concentrate on the personal aspect; how living during these political conditions affects the everyday lives of people whose domestic bliss is shattered by them. It’s an approach that works for the better and remains free of simple moralising and judgement. A masterpiece by any yardstick.

Monday 28 May 2007

Third Part of the Night (Poland, 1971, Andrzej Zulawski)

Recently released for the first time ever on DVD by the excellent Second Run label, this screening preceded a Q&A with Zulawski, who was on fine form, and both insightful and revealing about this film and the rest of his work. Zulawski’s debut is partly based on the experiences of his father during the Second World War, and it’s quite staggering how this nightmarish world could possibly have been born out of real events in any way. The protagonist, Michael, is recuperating in the countryside after an illness, with his wife and son also present, although this is also for their own safety since the German invasion has made Warsaw too dangerous for them. After a walk one day, he returns to find his wife and child murdered with cruel abandon by German soldiers.

Recently released for the first time ever on DVD by the excellent Second Run label, this screening preceded a Q&A with Zulawski, who was on fine form, and both insightful and revealing about this film and the rest of his work. Zulawski’s debut is partly based on the experiences of his father during the Second World War, and it’s quite staggering how this nightmarish world could possibly have been born out of real events in any way. The protagonist, Michael, is recuperating in the countryside after an illness, with his wife and son also present, although this is also for their own safety since the German invasion has made Warsaw too dangerous for them. After a walk one day, he returns to find his wife and child murdered with cruel abandon by German soldiers.This encourages him to join an underground collective, but when his co-conspirator is killed, Michael has to run for his life. In a twist of fate, another man is mistaken for him, and is shot on a winding staircase; a scene that was later reprised in the climax of Zulawski’s ‘Possession’, filmed a decade later. Guilt-ridden, he finds the man’s wife, only to discover she is the double of his own dead wife (doppelgangers were a central feature of the aforementioned ‘Possession’). She is on the verge of giving birth, and he assists with the delivery of the child, which triggers flashbacks of his own son being born.

Michael then seeks to replace the man who was mistaken for him (who is still alive, but was taken by the Nazis and routinely interrogated and beaten), and look after his wife’s double and her child, which allows him to cope with the guilt of her husband’s fate and also the death of his own wife and child. More flashbacks reveal the lurid origins of their relationship; that Helena had been married and Michael destroyed this marriage by conducting an affair with Helena (their love is declared in a superb 360° swirl of the camera). In order to provide for his new family, Michael works at a clinic that is developing a cure for typhus, which includes feeding lice, which is precisely what Helena’s first husband had done.

Making love to his wife’s double, she explains that they are “reconciled in people who aren’t us”. As the German advance continues, everyone else in Michael’s life is dying; his sister, a nun, is captured by the Germans and taken away, his hysterical father sets his house on fire, and his fellow accomplices in the underground are targeted. Whether it is out of guilt or just curiosity, Michael resolves that he must seek out the man mistaken for him, which is suicidal in itself. In a hallucinatory conclusion, he finds the man in the hospital chained, beaten, but smiling. Escaping through a life shaft, he reaches the morgue, which has a dead body ominously lying beneath sheets. When he looks at who the dead body is, he is finally reconciled with himself.

The final scene of ‘Third Part of the Night’ is shocking, but probably won’t be too unique to viewers as it’s been borrowed in subsequent films. As already mentioned, Zulawski’s own ‘Possession’ borrows various conceits from this film; the use of doubles and mistaken identity in particular. Are these doubles different ‘versions’ of Michael and Helena, whose lives exist in a different time and place entirely, but are interrupted when Michael and his double are mistaken for each other? As his own family are dead, does Michael have to put things right by assuming the role of this man? His overwhelming sense of guilt dictates that he must. However, in a time when all those around him are dying, Michael’s own mortality is equally perilous. Death ominously hangs in the air. In his final attempt to resolve natural order, he meets the conclusion that was always destined for him. The sight of his dead self could be either a premonition or a vision of what should have been – you could reasonably argue for both interpretations, but it concludes a nightmarish and hypnotic film perfectly. Michael’s life has indeed come full circle.

Sunday 27 May 2007

This is England (UK, 2006, Shane Meadows)

So much is written about British home grown cinema and its current state. It currently appears that two styles of films are being made and released widely; Guy Ritchie style gangster films that follow the path of ever diminishing returns and usually keep Danny Dyer’s ludicrous acting career afloat, or low-rent American Pie style ‘gross out’ films such as ‘I Want Candy’, which make the American precursors to these look like a golden age of comedy. So where can cinema that reflects Britain as it truly is be found? The films of Shane Meadows, as well as Pawel Pawlikowski, wouldn’t be a bad place to start. Certainly, these are the two most interesting British directors currently making films. Their films are inspired by the more social realist and ‘kitchen sink’ approaches of Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, but they’re also modern, nod partly to American cinema, and are partly autobiographical.

So much is written about British home grown cinema and its current state. It currently appears that two styles of films are being made and released widely; Guy Ritchie style gangster films that follow the path of ever diminishing returns and usually keep Danny Dyer’s ludicrous acting career afloat, or low-rent American Pie style ‘gross out’ films such as ‘I Want Candy’, which make the American precursors to these look like a golden age of comedy. So where can cinema that reflects Britain as it truly is be found? The films of Shane Meadows, as well as Pawel Pawlikowski, wouldn’t be a bad place to start. Certainly, these are the two most interesting British directors currently making films. Their films are inspired by the more social realist and ‘kitchen sink’ approaches of Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, but they’re also modern, nod partly to American cinema, and are partly autobiographical.‘This is England’ is Meadows’ most autobiographical and mature work to date, and describes Meadows’ own childhood flirtation with skinhead gangs, both in their purist and racist forms. The young protagonist Shaun is based on the director, whose dad has just died in the Falklands, and is raised alone by his mother. Bullied by older boys at school, he falls in with a crowd of teenage skinhead delinquents who are more or less harmless and provide both a respite to the victimisation he feels at school and also a mentoring and parental support. Shaun shaves his hair and joins the gang in destroying derelict houses, but the future of this gang all changes when Combo, a friend of Woody, the leader of the gang, returns from jail. We learn that Woody was somehow involved in Combo’s time in prison – perhaps taking the full rap for something.

Combo is now a racist, speaking the vile language of the National Front, even in front of the gang’s one black member, Milky. The gang then splits; some staying with Woody, others joining Combo’s more violent and prejudiced outfit. Crucially, Shaun sides with Combo, who he sees almost as a surrogate father. Combo’s gang attends National Front rallies, whose leadership seem like thugs in suits, and call for people to reclaim their country, though this manifests itself in robbing Asian shopkeepers and intimidating Asian children.

Combo is a very complex creation indeed, pent up with hatred and aggression, and like a time-bomb waiting to go off. We want to understand where this frustration comes from, though Meadows is reluctant to provide simple answers. He is in love with Lol, Woody’s girlfriend, with whom he had a one night stand which she wants to forget, and she rejects him once more. Combo’s explosion of violence comes not against Woody, but against Milky. It seems to be born out of his lack of something; a lack of family or sense of belonging, both of which Milky has in abundance and takes pride in. This is more than Combo can handle. How can someone whose roots are not English enjoy much more than he does in his own country? I should warn that this attack is sustained and brutal, but it is right that it should be so. This part is based on an incident that really occurred, and Meadows claims it is this that really woke him up to what his gang were truly capable of, which he then left.

Some have argued that Meadows is too ambivalent and not condemning enough of the skinhead movement that became overtaken by a racist element in the early 1980s. For the film to have credibility though, Meadows has to show why they might be attractive for both him and others, rather than just portray them as cartoonish thugs. The members of these gangs, like Combo, are missing something which either the gang mentality or ideology can compensate for. Meadows draws parallels between these incidents and the war in the Falklands with a montage of victorious British soldiers and outnumbered, under-equipped, and defeated Argentinean teenagers. It hardly seemed a fair or just fight. Shaun’s final rejection of country and the insidious characteristics of national pride are shown when he throws the Union flag given to him by his father into the sea.

Meadows’ period detail is accurate, though there is the odd anachronism, such as footage of the miners’ strike, which had yet to start when the film was set in 1983. An opening montage of Thatcher, Knight Rider and Roland Rat reinforces this, and provides context. Meadows captures a divisive time; when the policies of the Thatcher governments decimated working class communities, and many looked for convenient and defenceless scapegoats (immigrant communities). ‘This is England’ is a powerful rights of passage film, and unfortunately the language and violence (which could not have been softened for fear of completely undermining the film) ensures that the audience it really ought to reach, might not get to see it, which is a shame as it has definite educational value. Now why is public money being spent on the films I mentioned in my opening paragraph, instead of more films like this?

Saturday 12 May 2007

Senses of Cinema Top Tens

http://www.sensesofcinema.com/

Readers are encouraged to submit their top ten films of all time, and new batches are published in each issue.

In the latest issue, they have posted mine.

http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/top_tens/index.html#kwilson

Monday 30 April 2007

El Topo (Mexico, 1970, Alejandro Jodorowsky) and The Holy Mountain (Mexico/USA, 1973, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

When you’ve seen a Jodorowsky film, you’re not going to forget it in a hurry. The strange imagery, philosophies and set pieces which seem entirely random and disconnected have a lasting impact; it stays with you regardless of whether you like it or not. These films were released during the popularity of LSD and Eastern philosophies amongst certain Western youth subcultures; it’s really no surprise that The Beatles were reportedly taken with ‘El Topo’, as were much of the Hollywood new wave of the time (Dennis Hopper for instance). Their lawyer, Allan Klein, even part financed ‘The Holy Mountain’, though ensured it remained undistributed and unreleased for more or less three decades afterwards (a DVD release of both films is imminent). I’m not sure the films have aged very well, or would strictly mean that much to those outside its obvious demographic. Both are surreal journeys, often beautiful, often disturbing, but totally unique.